James Harrod was one of those early explorers, first coming to the Bluegrass region of Central...

Part 1: THE BEGINNINGS OF KENTUCKY SETTLEMENT

The land we now know as Kentucky was once part of Virginia. For many years the Appalachian Mountains were a practically impermeable barrier to settlement, and there was so much land available east of the mountains that there was no practical need to traverse them. However, the urge to explore and exploit natural resources was strong. The Cumberland Gap, a pass near the spot where present-day Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee meet, was used by wildlife and also native American tribes: white explorers called the trail “the Warrior’s path.” https://www.nps.gov/cuga/learn/historyculture/warriors-path.htm

Of course, Native Americans knew all about The Great Meadow of central Kentucky, which we now know as the Bluegrass region, though at the time of white settlement it was considered a shared hunting ground and no native tribes actually lived on the land. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232563896.pdf As tensions grew before the American Revolution, both the British and Colonials appealed to native groups for their support: many looked at the Colonists as a greater threat, and chose to side with the British, who could provide valuable trade goods (guns, metal tools, cloth, etc.) to the native tribes. https://www.amrevmuseum.org/big-idea-5-native-american-soldiers-and-scouts#:~:text=In%201775%2C%20when%20the%20Revolutionary,on%20American%20Indians%20for%20support.

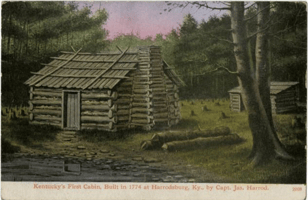

Some early white travelers went to the wilderness as missionaries, but most went with the goal of making money in some way: trading with Native Americans could be lucrative but was difficult, as developing trusting relationships with native tribes was particularly risky at that time. One of the most attractive resources west of the mountains was land. Dr. Thomas Walker, a physician from Virginia, was an investor in The Loyal Land Company and hoped to get rich off of reselling a great deal of it. He organized and led an expedition through the pass and across thousands of acres of eastern Kentucky and Ohio, and left the oldest surviving written journal of such expeditions. Theis team of explorers named the Cumberland Gap and the Cumberland River, and built the first cabin recorded as built by a white man in Kentucky in 1750, near Barbourville, about 30 miles from the Cumberland Gap. After exploring thousands of acres they returned to Virginia, reporting that the land was too rugged to be settled: they didn’t go far enough west to discover the area known at the time as The Great Meadow, what we call the Bluegrass region of central Kentucky. A cabin representing that first structure stands in Thomas Walker State Park in Barbourville. https://parks.ky.gov/barbourville/parks/historic/dr-thomas-walker-state-historic-site

Whitney Todd, “First Cabin in Kentucky,” ExploreKYHistory, accessed April 22, 2023, https://explorekyhistory.ky.gov/items/show/653.

The first documented longhunt began in 1761. Longhunters stayed in the rich central area of Tennessee and Kentucky for months hunting buffalo, bear, deer, and elk, to take piles of valuable skins back east. While earlier long hunts in Virginia lasted from October until March to get the highest quality animal skins, destined for export to Europe. Over time game animals were pushed west by human settlement, and additional travel across the mountains meant that longhunts would last up to two years. http://www.mtnlaurel.com/history/1591-the-border-series-the-long-hunters.html A good hunt was worth a small fortune, bringing in more cash than decades of farming, but not all longhunts were good. One of Daniel Boone’s hunts in 1769 was interrupted by a group of Shawnee who confiscated the many skins he had accumulated, on the grounds that he had poached animals on their land. On a later mission that included Daniel Boone and his grown son, Native Americans intercepted the group including the younger Boone who was killed, slowly and painfully: Daniel recognized the voice of his son but could do nothing to save him. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232563896.pdf

We are lucky that William Calk kept records of his long hunt into what would become Kentucky in 1776.

https://archive.org/stream/jstor-1886194/1886194_djvu.txt

The first land grants in this area that would later become Kentucky were made in 1773, and in the following year thanks to a much-reduced Native American presence south of the Ohio River 200,000 acres of land were surveyed. Governor Dunmore’s proclamation that “any settler shall have Fifty acres at least, and also for every Three acres of cleared land, Fifty acres more and so in proportion” caught the attention of many landless laborers, and by 1775 there was a surge of settlers coming to claim a stake in the fertile new land. The Transylvania Company, a group of private investors, negotiated a purchase of land from the Cherokee tribe in 1775 and fueled tremendous excitement in settling the land, though the land sale was later declared illegal by the Virginia government on the grounds that Virginia had already purchased the land from a different tribe. Beginning in 1779 Revolutionary war veterans who served for three years in Continental or State forces could be awarded land grants of 100 acres or more based on the soldier’s rank, many officers receiving more than a thousand acres apiece.

https://lva-virginia.libguides.com/bounty-claims#:~:text=The%20federal%20government%20also%20granted,and%20the%20qualifications%20were%20reduced. And https://www.sos.ky.gov/land/resources/articles/Documents/HammonInitialLandAcq.PDF page 25.

Colonel Henderson, leader of The Transylvania Company, was not happy about the easy claims to free land because that limited his ability to sell land to settlers: he wrote that “men had not contented themselves with the choice of one tract of land a piece, but had made it their entire business to rude through the Country marking every piece of Land they thought proper, built cabins, or rather hog pens to make their claims notorious, and by that means had Secured every good spring in a Country…” https://www.sos.ky.gov/land/resources/articles/Documents/HammonInitialLandAcq.PDF

Some men came with the intent to stay, others made minimal improvements to a piece of land without surveying or registering the claim, with the intent to resell it as quickly as possible. This haphazard settlement resulted in many competing land claims, with multiple people believing they owned the same piece of property, which would later affect many pioneer families including the Lincolns. ”there’ll be bloodshed soon – Hundreds of wretches come down the Ohio & build pens or cabins, return to sell them; the people come down & settle on the lands they purchase; these same places are claimed by someone else, & then quarrels ensue…. Many have come down here & not stayed more than 3 weeks, & have returned home with 20 cabins apiece & so on.” https://www.sos.ky.gov/land/resources/articles/Documents/HammonInitialLandAcq.PDF page 8

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transylvania_Colony#/media/File:Wilderness_road_en.png

The first white settlers in what we know now as Kentucky included Daniel Boone, a hunter familiar with the area, who was paid to locate the best place for a road across the Appalachian Mountains from Virginia. Thanks to his guidance, a team of about 30 axmen cut the Wilderness Road (though little more than a trail at the time) through the Cumberland Gap and miles of brush and cane (a bamboo-type plant), offering thousands of settlers from Virginia and North Carolina a comparatively easy 200-mile trail into the western wilderness and to Boonesborough. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transylvania_Colony If travel conditions were good and the party was not slowed by children, livestock, or a quantity of baggage, this trip could be made in 2-3 weeks. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232563896.pdf pg 25.

“One of the earlier travelers, a British visitor writing in 1775, although young, unencumbered by numerous possessions, and without family responsibilities, frequently found the journey challenging. "These vast ridges of mountains which we crossed rendered this day's journey extremely severe and fatiguing both for ourselves and our horses, although we did not travel more than about thirty miles," he wrote. "In the morning we undertook the hazardous task of fording Clinch's River, and accomplished it after several plunges, as usual, over our heads." His party prudently waited until the next day to climb Cumberland Gap in order to get some rest, "for we always alighted and led our horses up these prodigious steep, and perilous ascents." The descent of Cumberland Gap, also steep, presented a different set of difficulties: "This northwest side was almost bare of soil; ... and quite incumbered with rocks and loose stones, which exceedingly impeded our way, and retarded our progress." Pine Mountain Gap was "almost entirely covered with universal and impenetrable thickets of laurel." Getting past the mountains did not put an end to the hard work of travel, for although "all this country to the westward ... appeared as a beautiful level extended far beyond the view, and all the horizon was as straight and even as a line, or as the ocean itself, yet now we had descended into it we found it extremely broken, with abundance of rocks, and thickly intersected with water-courses." No man, woman, child, or beast could escape these difficulties.” https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232563896.pdf pg 29

Other early explorers and settlers came from western Pennsylvania by way of the Ohio River, and Fort Pitt (at modern Pittsburgh) was one of the most accessible sources of necessary supplies. This route should take about the same amount of time as the Cumberland Gap, though floating was much less strenuous than walking over dangerous and rocky paths and crossing numerous rivers. Over time this water route would be traveled frequently by persons bringing a family, household goods, or livestock. Flatboats were built for one-way traffic only, and could carry several families traveling together: if there were enough, a separate boat could carry the livestock. Solo travelers could be added to a larger group, who either paid for their passage with money or with labor. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232563896.pdf pg 8 - 16.

** insert drawing of flatboat from pg 15** https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232563896.pdf

Hazards of water travel included running into rocks and trees in the river, and running aground, which could happen unexpectedly as water levels fell; of course collisions had potential to damage the boats, leaving personal property and foodstuffs wet and moldy if lucky, or at the bottom of the river. Continuing on the river at night was dangerous, as was going ashore, which risked damage to the boat as well as exposure to attack from Native Americans. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232563896.pdf pgs 31-33.

Most boats would stop at present-day Maysville KY, so travelers would continue the last 60 miles to Lexington on the Limestone Trace, a winding path. https://maysville-online.com/features/61575/discover-the-history-of-kentuckys-limestone-trace Travel by land also left travelers vulnerable to attacks from Native Americans who lived on the north side of the Ohio River, as well as the usual challenges of travel in an area without a guide or clearly marked paths: a trip that should have taken only 3 days could turn into weeks and exhaust food supplies. A blockhouse was built at that landing in 1784 and the place became known as Limestone. Daniel Boone and his wife Rebecca operated a tavern there for a few years, doubtless providing advice and assistance to many immigrants. https://www.britannica.com/place/Maysville

Next Installment: The First Stations!